You may have heard of the Jennings Revolving Fund or Revolving Fund properties associated with Preservation of Historic Winchester, but you may not know exactly what that is and how that is different from the Historic District zoning and the Board of Architectural Review. Today, we’ll take a brief look at what revolving funds are and how they impact you.

What is a Revolving Fund?

At its most basic level, a historic preservation revolving fund is a pool of money which is used in some manner (purchases or loans) to buy or make improvements to a property. The money from those improvements “revolves” back into the fund either at the sale of the property to a new owner who will complete renovations or through repayments of the loans for renovation costs. The fund can then be used again and again to repeat the process.

At its most basic level, a historic preservation revolving fund is a pool of money which is used in some manner (purchases or loans) to buy or make improvements to a property. The money from those improvements “revolves” back into the fund either at the sale of the property to a new owner who will complete renovations or through repayments of the loans for renovation costs. The fund can then be used again and again to repeat the process.

The goal of the fund is not to make money by itself – although that can happen – but to give an endangered property the time or money boost needed to enact a preservation plan. In almost all cases revolving funds lose money through the expenditures necessary to buy, sell, and restore property. This financial loss is offset by the retention of important architectural and cultural resources, and the fund is financially replenished through gifts, pledges, and fundraising events.

History of Revolving Funds in Historic Preservation

Historic Charleston Foundation began what was likely the first historic preservation revolving fund in 1957 following their successful fundraising efforts to purchase the Nathaniel Russell house. The goal was to raise $100,000 to be used toward purchasing residential property in a concentrated area and to make facade improvements to tempt buyers to complete the renovation, with supporting goals of occasional commercial purchases, acquisitions for rental, and selective demolition of noncontributing elements in the historic district. The objective was not to buy and hold property in perpetuity to turn it all into museums or to pick select individual properties scattered about a large area, but to make concerted, organized efforts to improve one area of Charleston with the most effective and visible use of their funds. Aside from bequests, property gifts, and pledges, Historic Charleston Foundation used historic house tours to generate income.

Historic Savannah Foundation also found itself beginning a revolving fund almost by accident in 1959, when at the last moment Leopold Adler, II managed to negotiate a price for the land, then the bricks of the just-demolished carriage houses, then a price for the “standing” bricks in the Marshall Row houses. The main innovation of the Historic Savannah Foundation was to survey the city’s architecture, key it to Sanborn Maps, and determine the economic and cultural value of the historic buildings.

Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation began a revolving fund as part of their efforts in 1966. Pittsburgh’s angle was to rely on the architecture and history of the houses to help sell their need for preservation. A special focus was placed on turning around the Mexican War Streets area, which was rife with slum lords, overcrowding, and long-term residents fleeing the neighborhood because of the deteriorating conditions. The revolving fund was used to purchase property from the slum lords, stabilize the neighborhoods, and bring in a younger population as well as slowing the exodus of longtime residents. As overcrowding was a serious issue, part of the revolving fund’s mission in Pittsburgh was to provide assistance in relocating or subsidizing rents for low income tenants.

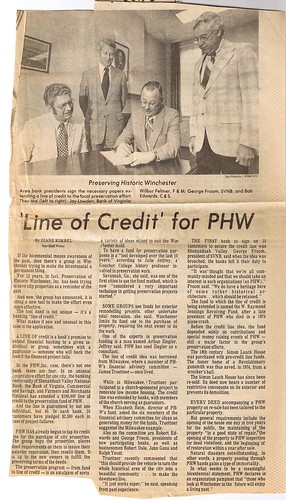

The Revolving Fund in Winchester

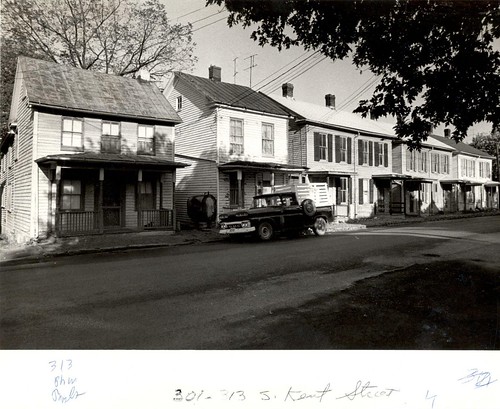

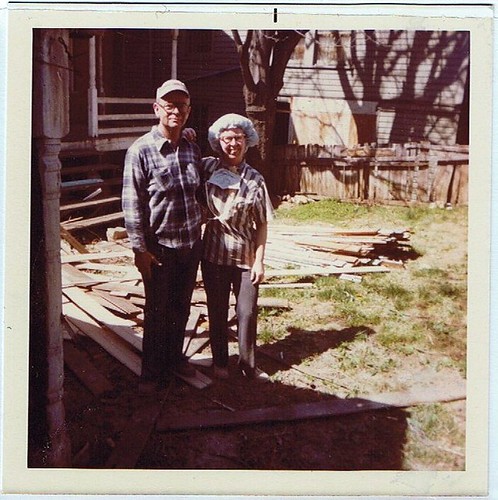

Ray Jennings introduced the idea of a revolving fund to PHW during his brief but vital period in Winchester. Modeled on the programs in Charleston, Savannah, and Pittsburgh, PHW primarily used the revolving fund to purchase very early log structures around the downtown that were threatened with demolition or severe neglect. South Loudoun Street was picked as the target area for its concentration of early log homes, its visibility, its vulnerability to demolition, and because of the truly appalling living conditions in many of these single family houses that had been converted to multiple apartments.

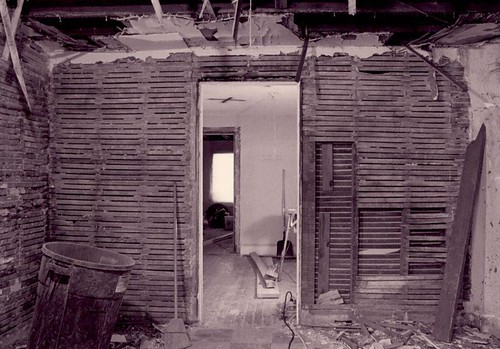

Like the example programs, work was concentrated on the exterior of the building to maximize visibility and investment, like the selective demolition at the Simon Lauck House to reveal the log construction under the Victorian-era additions. The architectural survey of 1976 was led in part by the same professor who had led the Savannah inventory, with one of the goals being to use the survey to identify potential revolving fund purchases. In the sale of the homes, their architectural features and history, and later tax incentive opportunities, were used in the marketing as selling points. Instead of using photographs, artists created line drawings of the properties for the sale flyers to spark a buyer’s imagination.

Like the example programs, work was concentrated on the exterior of the building to maximize visibility and investment, like the selective demolition at the Simon Lauck House to reveal the log construction under the Victorian-era additions. The architectural survey of 1976 was led in part by the same professor who had led the Savannah inventory, with one of the goals being to use the survey to identify potential revolving fund purchases. In the sale of the homes, their architectural features and history, and later tax incentive opportunities, were used in the marketing as selling points. Instead of using photographs, artists created line drawings of the properties for the sale flyers to spark a buyer’s imagination.

To make sure the houses were sold to owners who would renovate and not demolish the structures, protective covenants were added to the deeds. In general the covenants pertain to the exterior appearance and upkeep of the properties, as well as a provision that PHW be notified with a right of first refusal when the property came up for sale again in the future. To date approximately 80 properties have either been bought and resold or had covenants voluntarily donated to PHW. The majority of these properties are within the Winchester Historic District, with a few just outside the boundaries, and one property in Frederick County.

How can I tell if my property has protective covenants held by PHW?

All of the properties with oversight by PHW and their matching deeds with the covenants listed are available online at PHW’s website, listed by street.

What if my property has protective covenants held by PHW?

There are two main obligations for all such properties. The first is that, like properties in the Winchester Historic District which are subject to Board of Architectural Review approval, PHW requires a sign off on exterior changes to the property (such as additions, demolitions, replacement materials, and paint colors) before changes are made. Certain buildings have similar restrictions on interior features like doors, trim, mantels, or floorboards of exceptional significance to the home.

There are two main obligations for all such properties. The first is that, like properties in the Winchester Historic District which are subject to Board of Architectural Review approval, PHW requires a sign off on exterior changes to the property (such as additions, demolitions, replacement materials, and paint colors) before changes are made. Certain buildings have similar restrictions on interior features like doors, trim, mantels, or floorboards of exceptional significance to the home.

The second obligation is that during certain property transfers, PHW holds a “right of first refusal.” In general, this requirement is satisfied by the seller or the real estate agent contacting PHW with the asking price for the property. PHW will prepare a form letter to note PHW will not exercise the right of first refusal for the transaction. Depending on your legal requirements, PHW may also be included as an additional signer on the deed, or notarized forms or addenda may be filed with the deed.

What kind of information do I need to submit to PHW to make exterior changes to a property with protective covenants?

Because almost all of the properties with covenants held by PHW are also subject to the same review process as the Board of Architectural Review, we suggest you simply submit an additional copy of the same materials you prepared for your BAR application to PHW with a cover letter stating your intentions. You may bring larger documents to the PHW office at 530 Amherst Street or email all your material to phwi@verizon.net (maximum per-email size limit is 20 MB). Requests for exterior changes are reviewed as they are received by a committee of PHW board members.

I have other questions or need PHW to sign off on a right of first refusal; whom do I contact?

The PHW office may be reached at (540) 667-3577 or phwi@verizon.net. In general, a member of the PHW board is required by the protective covenants to sign on behalf of PHW. Please allow for one to two days to arrange for a PHW representative as a signer.

Information on the history of the three early historic preservation revolving funds taken from Revolving Funds for Historic Preservation by Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr. et al.