This post is part of the series of history posts in celebration of PHW’s 50th Anniversary year. For the newcomers to this list, you may catch up on the earlier posts in this series at the PHW blog under the tag 50th Anniversary.

At long last, in May 1988 the final contract between the City and PHW to allow the organization a chance to find a new use for the “ugly” Kurtz Building was finalized, though with a few important strings attached. The City would not turn over the building to PHW if and until the work was completed on time — should PHW fail to complete the rehabilitation by 1989, the City would not convey the building to PHW. Frederick County still retained building rights for the land surrounding the Kurtz as well. Although unlikely, there was a possibility the County could decide to build on the lot and thereby raze the Kurtz. (1)(2)

At long last, in May 1988 the final contract between the City and PHW to allow the organization a chance to find a new use for the “ugly” Kurtz Building was finalized, though with a few important strings attached. The City would not turn over the building to PHW if and until the work was completed on time — should PHW fail to complete the rehabilitation by 1989, the City would not convey the building to PHW. Frederick County still retained building rights for the land surrounding the Kurtz as well. Although unlikely, there was a possibility the County could decide to build on the lot and thereby raze the Kurtz. (1)(2)

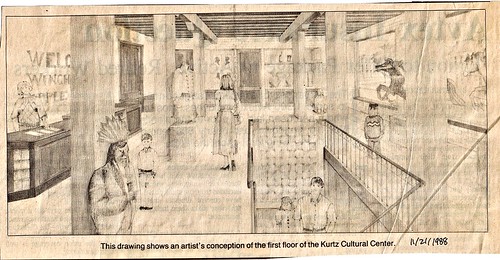

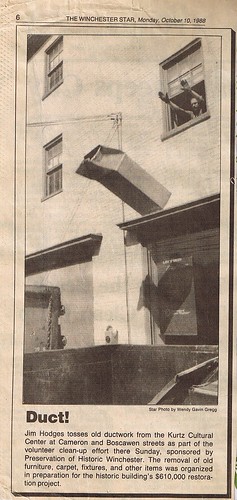

Despite the gravity of the situation, spirits at PHW were high and optimism abounded. Thomas Kamstra and Eric Snyder were brought on board as architect and project manager and public input sessions were held with them to plan for the building’s future uses.(3)(4) Elaine Rebman was hired as the director for the Kurtz Cultural Center.(5) And in keeping with PHW’s tradition of hands-on volunteerism, a demolition party manned by volunteers cleared out the interior of the Kurtz.(6)

With this groundwork laid, it was time for PHW to make the most of the opportunity to save the Kurtz.(7) The $100,000 in state money from the Virginia Preservation Fund came through, after being chosen from a pool of 120 other applications. Local businesses and individuals began making contributions for the named rooms in the Kurtz Building, and the fundraising events began with an art show by Geneva Welch and an oriental rug exhibit and sale. Shenandoah University donated a performance of “The Pirates of Penzance” to the fundraising efforts, and PHW was given permission to make prints of the Edward Beyer painting “A View of Winchester,” which is now on display at the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley.(8) (9)

This pattern continued through 1989 and 1990. PHW was granted an extension for the exterior and structural stabilization phase due to complications from asbestos removal, but the fundraising events continued full steam, with more state grants, more donations from local businesses, and more art, antique, musical, and fashion shows. A playhouse-sized model of the Kurtz Building was even constructed by local high school students and raffled as a fundraiser during the 1989 Potato Hill Street Festival.(10) The project at last began to seem like a reality in April of 1990, when the building was opened for a hard hat tour to show off the structural work and the mysteries uncovered in the building.(11)