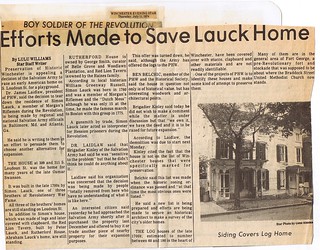

At last, with a trained revolving fund director and a recharged membership united behind the memory of Ray Jennings, PHW was ready to tackle a project through the Revolving Fund. That property just happened to be the Simon Lauck House at 311 South Loudoun Street. In 1974, the Salvation Army had purchased the duplex at 309-311 South Loudoun Street with an eye toward demolishing the building to expand the operations in their headquarters at 303 South Loudoun Street. PHW was interested in preserving the otherwise unassuming-looking building, because preserved inside the duplex was the log cabin of a famous early owner, Simon Lauck.

At last, with a trained revolving fund director and a recharged membership united behind the memory of Ray Jennings, PHW was ready to tackle a project through the Revolving Fund. That property just happened to be the Simon Lauck House at 311 South Loudoun Street. In 1974, the Salvation Army had purchased the duplex at 309-311 South Loudoun Street with an eye toward demolishing the building to expand the operations in their headquarters at 303 South Loudoun Street. PHW was interested in preserving the otherwise unassuming-looking building, because preserved inside the duplex was the log cabin of a famous early owner, Simon Lauck.

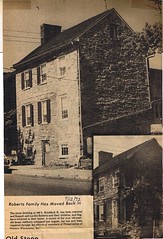

The duplex had not originally been listed in PHW’s 1966 list of worthy buildings in part because the Victorian-era makeover had been too complete, making the house look “younger” than it actually was. The initial survey of Winchester had lacked many of the tools we now take for granted when researching area buildings, like Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. However, more intensive research uncovered the core of the building was much older and more important than anyone first guessed.

Simon Lauck, along with his brothers Peter (of Red Lion Tavern fame) and Abraham, was part of the Dutch Mess organized in Winchester during the Revolutionary War. According to local legend, the Lauck brothers were part of Daniel Morgan’s honor guard and acted as translators with captured Hessians soldiers. After the Revolutionary War, the brothers returned to Winchester, each taking up residence on South Loudoun Street. Simon set up his gunsmithy on this property. Over the years, the house was expanded, then later updated with Victorian gingerbread details. By the 1970s, the Simon Lauck house was in decline, leading to its potential status as a playground.

Simon Lauck, along with his brothers Peter (of Red Lion Tavern fame) and Abraham, was part of the Dutch Mess organized in Winchester during the Revolutionary War. According to local legend, the Lauck brothers were part of Daniel Morgan’s honor guard and acted as translators with captured Hessians soldiers. After the Revolutionary War, the brothers returned to Winchester, each taking up residence on South Loudoun Street. Simon set up his gunsmithy on this property. Over the years, the house was expanded, then later updated with Victorian gingerbread details. By the 1970s, the Simon Lauck house was in decline, leading to its potential status as a playground.

When PHW approached the Salvation Army to purchase the Simon Lauck house, the initial offer was only for the logs after the house was demolished. This offer was not good enough for PHW, sparking a long and heated back-and-forth negotiation with regional Salvation Army leaders. In the end, the negotiations succeeded and PHW owned its very first historic building.

The plan at the time was to restore the building’s exterior to its appearance circa 1790 as a proof to Winchester that many of the “Victorian” houses in the Potato Hill area in fact contained a much older log nucleus. To achieve this, a substantial portion of the house was removed, reducing it from a duplex to a single residence and stripping most of the exterior away. PHW volunteers did a great deal of the hands-on work at the Simon Lauck house, as documented by Virginia Miller.

In 1976, the log cabin was exposed and a new owner purchased the building from PHW and completed the work in making the former duplex a charming office. Although the ride was bumpy, in the end one of Winchester’s oldest log buildings was preserved and still serves as a reminder of our frontier roots just blocks from Old Town.

|

| View more progress pictures of the Simon Lauck House at Picasa |

For more reading on the Lauck family and gunsmithy, investigate some of the following links:

Lauck Family Genealogy

A Simon Lauck Buck and Ball Gun

A John Lauck Rifle at the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley