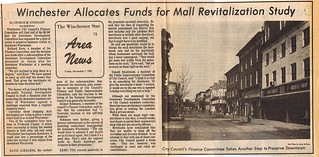

As mentioned last week, Winchester’s downtown was approaching a time of reckoning in 1980. Three mall developers were looking toward construction of a regional shopping mall in Winchester’s vicinity, and the anchor stores of the downtown – Leggett’s, Sears, and JC Penney’s – had all expressed interest in moving to this new location. Nearby cities that had not invested in their downtowns were experiencing a rapid decline in the older commercial districts, with vacant storefronts, vagrants and drug dealers, and arson and vandalism problems. Winchester hoped to steer away from that path of decline through proactive assessments and actions. (1)

As mentioned last week, Winchester’s downtown was approaching a time of reckoning in 1980. Three mall developers were looking toward construction of a regional shopping mall in Winchester’s vicinity, and the anchor stores of the downtown – Leggett’s, Sears, and JC Penney’s – had all expressed interest in moving to this new location. Nearby cities that had not invested in their downtowns were experiencing a rapid decline in the older commercial districts, with vacant storefronts, vagrants and drug dealers, and arson and vandalism problems. Winchester hoped to steer away from that path of decline through proactive assessments and actions. (1)

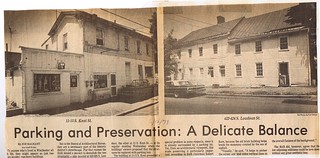

The special tax district that was put in place for the construction costs of the pedestrian mall was due to expire in 1983. Thoughts turned almost immediately to extending that tax and collectively using those funds to promote the downtown. More controversially, the tax could be expanded into an adjacent secondary district comprised of Piccadilly, Boscawen, Cameron, Braddock and Cork Streets. Proponents of this idea cited the tax would average about $500, or about the cost of a full page advertisement in the Winchester Star in 1980.

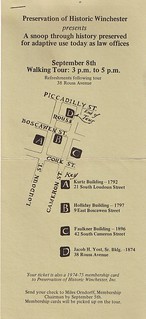

David Juergens, co-chair of the Downtown Development Committee studying this conundrum, laid out his thoughts on how an older downtown could adapt some of the ideas of the regional mall strategy. The pedestrian mall would have to become event and entertainment oriented, with attractions other than just shopping. A downtown administrator would be hired to coordinate among the merchants and paid for through the special assessment district and dues to the Retail Merchants Association. This was a similar strategy used by the shopping malls to keep a cohesive branding between the multiple stores. Vacant upper floors would be targeted to be filled and maximize the square footage of the downtown buildings. And as is fitting, he echoed the sentiments of architecture lovers everywhere: “We want people to come downtown where the architecture is real and the design honest.”

In November 1980, the National Development Council was hired to lay a financial plan for the downtown to compete against the expected regional mall. The other ideas of special assessment areas and a downtown manager to coordinate between all the merchants like the regional mall model were also met favorably. Efforts had previously been made to keep “alcoholics and slovenly dressed” away from the downtown via a dress code, but that law had been challenged and ruled unconstitutional. The other option was to turn the pedestrian mall into a private street, so that private security officers could be hired to patrol the area. (2) (3)

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the plan was keeping and expanding the special tax district. It was a unique idea and is reportedly the only such district in Virginia. Expanding the assessment into a secondary district caused grumbles, because most of the focus of the downtown goes into the Loudoun Street corridor, then as now. Businesses in the secondary area countered that they could use the money from that tax to individually promote themselves, or that the burden of the tax would end up raising the rents on their spaces to the point where they would need to leave the downtown. (4) Officials, including Katie Rockwood of PHW, spoke in favor of the tax supporting the commercial downtown. From PHW’s perspective, a strong downtown helped to fuel our own Revolving Fund efforts. Although most of those properties are residential, the 30 properties that had passed through the Revolving Fund at that time were cited as spurring $1.6 million in investments. Those properties could not have been so successful in an economically depressed downtown climate. (5)

Irvin Shendow responded with a lengthy open forum piece as well, citing some of the positive changes that had started to take place with the construction of the pedestrian mall. Restaurants had moved downtown, store vacancies declined between 1974 and 1980, and renovations of buildings were on the upswing after 1975. He also noted that although a new regional shopping center might be a tempting move, rents there are almost always higher than in a downtown. He cited an average of $12 to $15 per square foot of space in a mall, compared to $2 to $4 per square foot in the downtown. Add in the regional mall fees, often three to five times the fees paid by the downtown merchants, and he doubted a bump up in rents from the downtown tax would kill the downtown’s “competitive pricing edge.” (6)

Irvin Shendow responded with a lengthy open forum piece as well, citing some of the positive changes that had started to take place with the construction of the pedestrian mall. Restaurants had moved downtown, store vacancies declined between 1974 and 1980, and renovations of buildings were on the upswing after 1975. He also noted that although a new regional shopping center might be a tempting move, rents there are almost always higher than in a downtown. He cited an average of $12 to $15 per square foot of space in a mall, compared to $2 to $4 per square foot in the downtown. Add in the regional mall fees, often three to five times the fees paid by the downtown merchants, and he doubted a bump up in rents from the downtown tax would kill the downtown’s “competitive pricing edge.” (6)

At PHW’s Annual Meeting in 1981, Porter Briggs spoke on the future of Winchester’s downtown. Although he warned the shopping mall was inevitable and the downtown would change, the two could coexist. The challenge would be to keep the downtown vital during this transitional process.(7) In the long run, his prediction has been proven correct – but it did take a long time to get there. Check in next week for a look at PHW’s direct contribution to the downtown mall with a facade restoration project at the Huntsberry Building!