The music for this installment is “When Jesus Wept.”

Text from this installment has been adapted from “Textiles” by Tina Rabun and Theodora Rezba in the “Valley Pioneers and Those Who Continue” catalogue, and the “West of the Blue Ridge” promotional newspaper clipping collection and exhibit texts.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, many of the textile products used in the Colonies were imported from Britain. In the 1700s, the Industrial Revolution was transforming previously laborious hand-processes and increasing production speeds, so that British goods were relatively inexpensive and in steady supply. It was not until the Revolutionary War severed the supply that it became a patriotic duty to spin, dye, and weave textiles. (1)

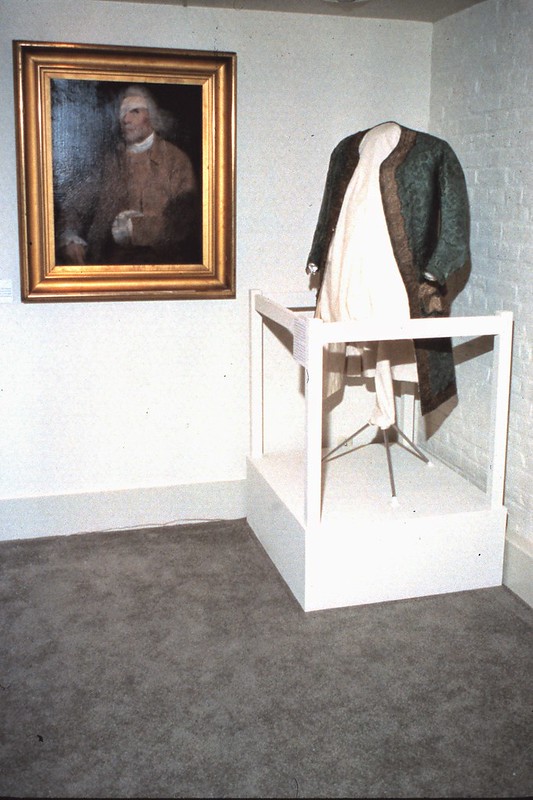

One well-known example locally of imported textiles is that of Lord Fairfax (1693-1781) during his time in Greenway Court. Andrew Burnaby observed of Lord Fairfax: “His dress corresponded with his mode of life, and, notwithstanding, he had every year new suits of clothes, of the most fashionable and expensive kind, sent out to him from England, which he never put on, was plain in the extreme.” This formal jacket probably was among those Fairfax imported from England.

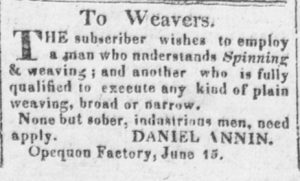

Locally-produced textiles exhibited in the “Valley Pioneers and Those Who Continue” show varied from a c. 1800 baby’s cap in cambric to sheets and pillow sham of flax c. 1870. Wool and cotton, however, provided the bulk of the material base for textile work. One of the county’s early woolen mills was located on the Opequon, and wool production remained a staple of Winchester’s employment until the closure of the Virginia Woolen Mill in 1958.

Handspun wool, not being very strong, was difficult to use as a warp; therefore not many blankets of all wool were woven until yarns could be spun commercially with the invention of the spinning jenny. Cotton was grown in Virginia prior to the Revolutionary War for domestic use, and many of the early surviving blankets use cotton threads for the warp. Flax, too, was grown in small quantities for personal use both for weaving linen and for producing linseed oil.

Almost every family in the Valley possessed a four-harness loom either brought from Europe or fashioned in America of hand-hewn logs. Both men and women did the weaving and the children were taught to card and spin the flax, cotton, and wool. Perhaps the most plentiful example of home weaving can be found in the family bedding. Three types of woven coverlets that were in common use in the Valley were the overshot, the double weave, and the jacquard.

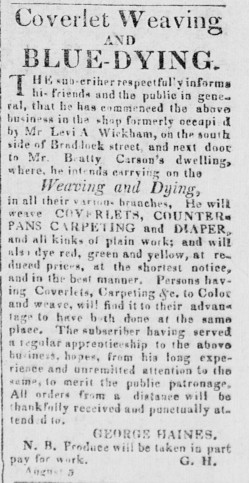

The overshot coverlet dates from the early settlement period and could be woven on a simple four-harness loom requiring minimal skills. In this weave, the weft threads usually form the pattern and “overshoot” the warp threads, forming floats across the background weave. The double weave style (1725-1825) is constructed so that two warps are joined so that the reverse side of the coverlet is a mirror image of the front. Thus the front would show a dark design on a light ground, while the back shows a light design on a dark ground. The jacquard coverlet required a specialized loom invented by a French weaver, Joseph Jacquard. The complicated mechanism that activated the harnesses allowed for the creation of intricate patterns like brocade and damask. The loom required two people to operate and made coverlet weaving a profession after the 1830s. Many of the professional weavers also offered dyeing services.

Quilts, the other major form of bedding, were largely made by women. The quilts themselves reflect the history of textile production in America, including home-woven cloth, souvenir fabric to memorialize important events, stitching techniques, patterns, and symbolic motifs important to the makers. Quilts are often a communal effort as well, and numerous signatures on one quilt can document the makers who lent their talents to the finished piece. Whole-cloth quilts of wool were produced from the late 1700s to early 1800s, but the familiar image of a quilt is likely that of multicolor pieced cotton. Early patterns were often simple geometric designs in rectangles, squares, and triangles. More elaborate designs could have been traced from newspaper or magazine patterns. The exact quilts displayed at the Kurtz Cultural Center in conjunction with Belle Grove Plantation were not well-documented, except for the “Spring Dreams” quilt, used as a raffle item. An Amish-made queen sized quilt, it features a white background decorated with circles and sprigs of flowers and vines in pastel pink, yellow, blue, and green. For more examples of American quilts, visit the National Quilt Collection at the National Museum of American History.

For a quilt made in Winchester by Amelia Lauck, wife of Peter Lauck (both previously discussed in the Portraiture entry), see the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts for a ca. 1823 quilt of cotton with appliques of flowers and birds.

While the bedding served daily needs, needlework could be used for education as well. The best example is that of a sampler. Known in Europe as early at the 16th century, the sampler reached its height of popularity in the 18th. Intended as a practical record of stitching patterns that could be added to and referred back to throughout a woman’s lifetime, it also came to serve a secondary use. Young girls were taught how to embroider at an early age, so their samplers were also used to practice letters, numbers, and more fanciful artistic expressions. A typical American sampler will contain various alphabetical forms, numerals, ornaments, and decorative borders. The stitcher may have included her name, the date, her school, figures like houses, pets, mottoes, and other personalized touches.

While the sampler was a relatively utilitarian piece that could be used as a reference guide, for some women the skills learned in stitching a sampler led to higher artistic expression. To explore the variety of needlework produced in early American history, you may wish to further explore the holdings of the Museum of Early South Decorative Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Join us next time for a look at furniture in the Valley on May 20.