Your music selection for this installment is “The Black Nag/Morrison’s Jig.”

In 1729-1730, Jacob Stover petitioned to create a 13th colony from the Virginia interior and bring Swiss-German farmers as settlers. This was a departure from the pattern of settlement in the east of Virginia, where grants were typically made to the wealthy English. The petition to the Colonial government struck at a fateful time. The Shenandoah Valley had been a place of escape for slaves fleeing a James River plantation in 1727. Although they were captured, the idea of the Valley becoming a haven for escapees had been planted in Virginia Governor William Gooch’s mind. This petition offered a way to settle the land and simultaneously not endanger the English elites.

Gooch denied the petition for the new colony, but approved immigrant farmers settling the Valley. The grants were to be made to “persons of low degree in life who are known amongst their equals as morally honest.” The stipulation was to have one family for every 1,000 acres. Attracted by the prospects of inexpensive and rich farmland, successive waves of Scotch-Irish and German immigrants settled in the valley.

“The necessary labors of the farms along the frontiers were performed with every danger and difficulty imaginable. The whole population of the frontiers, huddled together in their little forts, left the country with every appearance of a deserted region; and such would have been the opinion of a traveler concerning it, if he had not seen here and there some small fields of corn or other grain in a growing state.” — Samuel Kercheval, 1850

At first farmers in Old Frederick County raised crops and animals mostly for their own subsistence, but the rich soil and moderate climate combined to make the Valley the most important wheat-producing region in the Upper South by 1800. The change to wheat as a primary cash crop instead of tobacco as in eastern Virginia was said by Samuel Kercheval to have been inspired by the French Revolution in 1794, when all kinds of bread stuffs became enormously expensive. Wheat and flour production enriched the region for years afterward. In addition to wheat, local farms produced rye, oats, corn, and hay said to be “superior in quality and quantity” than average.

By the American Revolution the average Valley resident owned between 100 and 400 acres: increasingly, however, larger tracts of land were concentrated in the hands of a select few and tenancy was on the rise. To the west of the Opequon Creek, small family farms characterized the landscape: few people held more than 100 acres. On these small farms, families worked together in the fields. Samuel Kercheval remembered, “Many females were most expert mowers and reapers.” The yoke displayed from the Edward Durrell Collection, COSI, Ohio’s Center of Science and Industry, is the size worn by a woman or a child.

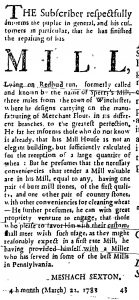

By contrast, the eastern Virginians who settled in east Frederick County in the 1780s and 1790s recreated Tidewater plantation society. These farms were set up with grand manor houses and large-scale agricultural production. Larger farms like Vaucluse outside of Stephens City could also have mills for flour production on site. Foreseeing the growth in agriculture, in 1785 Nathaniel Burwell and his partner, Daniel Morgan, established a merchant mill to buy, sell, and mill local grain and export flour in Millwood. Along with the positives of a successful commercial crop on the local economy, wheat and the large-scale agricultural endeavors helped spread slavery in the Valley. By 1800 approximately 5,000 enslaved African-Americans lived in Old Frederick County, a little more than 32% of the population.

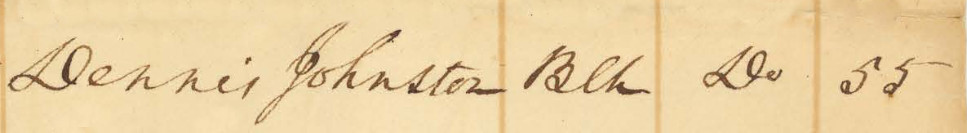

Slavery as an institution was not universally embraced by the Valley settlers. In 1782, Virginia law made the private manumission of enslaved individuals permissible. In an attempt to further this work, a group of Frederick County residents petitioned the Legislature in 1785 to outlaw slavery. Although unsuccessful in this early abolitionist attempt, Winchester became a haven for free African-Americans. Free African-Americans were required by law to register in their place of residence and to carry on their person at all times written proof of their status. Dennis Johnston was among the twenty-one Frederick County slaves manumitted by planter Robert Carter in 1799 and issued a certificate of freedom. His name, along with many other locally-recognizable names, appears in the Winchester 1833 Free Negroes and Mulattoes list available at the Library of Virginia.

Join us next time on November 19 to examine the commerce west of the Blue Ridge!