Welcome to a new series of articles that will be posted once a month from now until June 2022. As the PHW Office will be closed for all business on a number of Fridays for the next year, we thought this would be a perfect opportunity to highlight some of our older collected work from our Kurtz Cultural Center era. To produce and compile this series, we will be utilizing a number of the major exhibits hosted in the KCC during the 1990s, including the titular “West of the Blue Ridge” and “James Wood & the Founding of Winchester,” with additional information from the Shenandoah University exhibit “Valley Pioneer Artists and Those Who Continue” (itself the starting point for much of the “West of the Blue Ridge” exhibit) and others.

The posts will draw from exhibit texts, student and teacher guides to the exhibits, the digitized exhibit images, printed materials, press releases, and even the playlist of music that accompanied the “West of the Blue Ridge” exhibit. We hope this series will be nostalgic if you experienced it the first time, and informative if this is your first brush with this part of Winchester’s history.

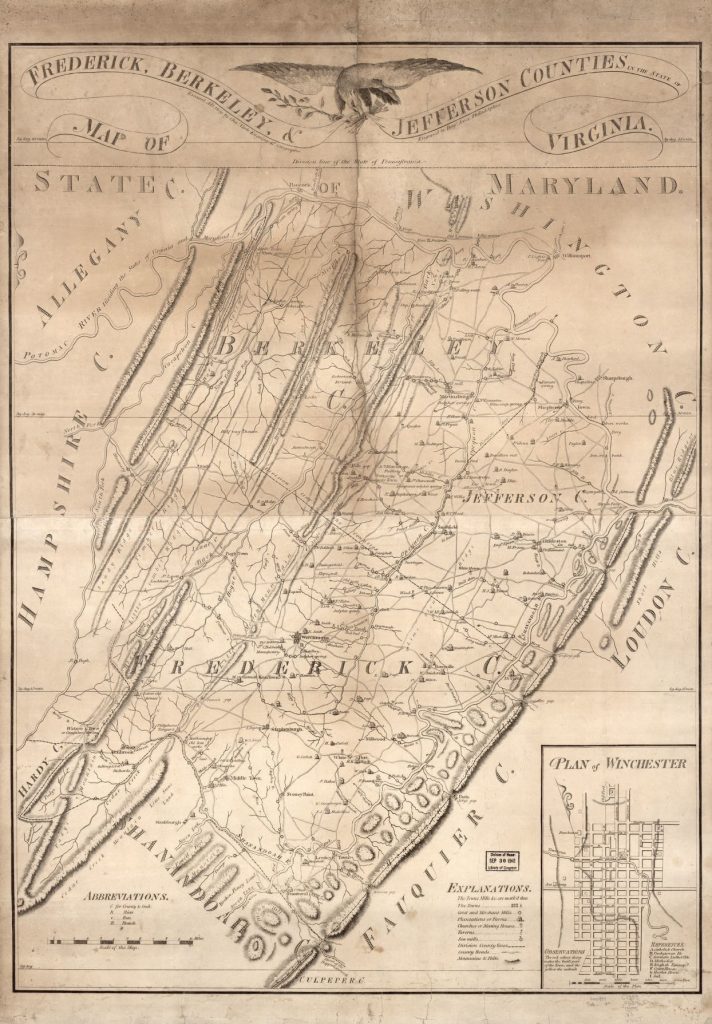

Believe it or not, Winchester, Virginia was once the “Williamsburg of the West.” In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the lower Shenandoah Valley was a prosperous and bustling crossroads for western migration. The region was a gateway to the southern backcountry and the new western territories: across Valley roads moved people, goods, services, and ideas. Winchester, founded in 1744, was already the largest and most significant city west of the Blue Ridge after the American Revolution, when Americans were looking to the west of their new nation.

The series’ name “West of the Blue Ridge” derives from a petition in which area residents asked the state legislature to build a courthouse in Winchester because they were tired of traveling east of the Blue Ridge. In the petition, local people emphasized that they were different from people east of the Blue Ridge. About 40 percent of the population at the time was non-English, and the settlers kept many of their traditions alive, including through their decorative arts.

Whether on a large plantation or a small farm in Old Frederick County, agriculture formed the daily lives of Valley residents. By the American Revolution greater and more specialized crop production had combined with increasingly diverse manufacturing to form a sophisticated local economy. As part of this commercial expansion, Winchester became a thriving city that enticed merchants, craftsmen, physicians, attorneys, and their families to settle there. Winchester flourished at the crossroads of transportation routes west and south, becoming the largest city west of the Blue Ridge. We’ll explore more of the town growth in next month’s installment on September 17!

“As this town is standing on the main roads to Pittsburg, Wheelen, Kentucky, Tennessee and the Warm and other springs, many strangers pass through it, which, besides the great intercourse it occasions, gives a gaity [sic] to the place, and has a great influence on the inhabitants.” – Charles Varle, 1809