In February 1969, plans were afoot for PHW to lead the charge against the demolition of the Conrad House by the Winchester Parking Authority. The committee, led by Julian Glass, Jr., focused on circulating petitions and organizing letter-writing campaigns in favor of the “phone or personal contact” which had been previously utilized. The steering committee included J.T. Kremer, Sr., Leonard Sirbaugh, Mrs. J. Pinckney Arthur, Clyde “Chip” Johnson, Betsy Helm, Mrs. Wayne Hogbin, and Dr. Garland Quarles.(1)

Petition drives were held in the George Washington Hotel. At least two angles were used on the petitions. The first concerned the lease executed between the City of Winchester and the Winchester Parking Authority. The petition asked for the City to resume control of the Conrad property and/or to hold a public hearing on the fate of the Conrad property. Reports indicate over 2,000 signatures were gathered and filled several full-page advertisements in the Winchester Star in March of 1969.

The letter writing campaigns included a piece from Dr. Quarles, explaining why the house was historically relevant, invoking some of the activities and important people who had a connection to the house.(2) Others echoed these sentiments, including Lillian Majally, who may have influenced PHW’s slogan with her heartfelt plea to save the best of the area’s past for future generations to discover their visual heritage.(3)

The letter writing campaigns included a piece from Dr. Quarles, explaining why the house was historically relevant, invoking some of the activities and important people who had a connection to the house.(2) Others echoed these sentiments, including Lillian Majally, who may have influenced PHW’s slogan with her heartfelt plea to save the best of the area’s past for future generations to discover their visual heritage.(3)

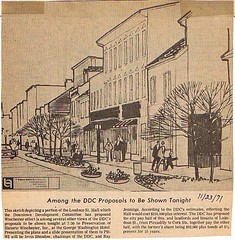

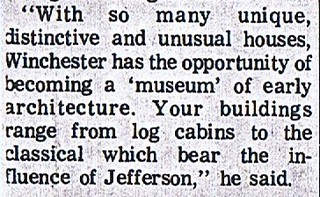

PHW’s President Lucille Lozier spoke of the potential for tourists to appreciate Winchester’s buildings and their palpable connection to early American history and culture.(4) Others, like Anne Williams, suggested new community-minded uses for the Conrad House, like a daycare center.(5) More often, the building was suggested as being incorporated into new government offices, used as a residence for visiting dignitaries to the city, or operated as a museum. Alternative parking options were discussed, such as constructing a double or triple decker parking garage on another site.(6) In an idea which may seem scandalous to propose today, PHW members even pitched the idea to Council to level Rouss City Hall for the parking lot instead (remember that Rouss City Hall was deemed both too young for being constructed after 1860 and infeasible to rehabilitate at the time).

As the very public efforts to block the demolition of the Conrad House wore on, the timbre of the letters became more exasperated. Many letters cited how the Council had refused to listen to their constituents on this matter despite over 2,000 signatures on PHW petitions to retain the building, and how the Council seemed to be driven by the wishes of the merchants for parking over the wishes of the citizens for preservation.The existing lots were cited as rarely being at full capacity, so the issue to demolish the house was not the pressing need it was made out to be. Also cited was the “pass the buck” maneuver for the Council to turn the fate of the Conrad House over to the Winchester Parking Authority. Some letters even correctly cited the Kurtz Building would be bought and singled out for demolition for more parking on that site in the future.(7)(8)(9)(10)(11)

The letter writing and petitions were not the only efforts undertaken by PHW. Efforts had been made for multiple years for PHW to receive authorization from the City or WPA to perform studies on the Conrad House to determine possible future uses for the building.(12) Even though the City refused these offers for studies, PHW still reached out to representatives from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Virginia Landmarks Commission, and other architecture experts for their input on the value of the Conrad House. Offers were made for PHW to raise the funds to fix the house’s leaking roof and to hire engineers and architects for the project. Attempts were made to list the building on the National Register of Historic Places to block the use of Federal funds in the construction of the parking lot. Injunctions were sought for the illegal tree-cutting on the Conrad Hill property, and efforts were made to appeal the Board of Architectural Review being cut out of the process for the Conrad House. As a final attempt, shortly before the demolition PHW ran a series of large advertisements in the Winchester Star alerting taxpayers as to how their money had been used to purchase the Conrad House, and how their money was funding this parking lot against public wishes.

The letter writing and petitions were not the only efforts undertaken by PHW. Efforts had been made for multiple years for PHW to receive authorization from the City or WPA to perform studies on the Conrad House to determine possible future uses for the building.(12) Even though the City refused these offers for studies, PHW still reached out to representatives from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Virginia Landmarks Commission, and other architecture experts for their input on the value of the Conrad House. Offers were made for PHW to raise the funds to fix the house’s leaking roof and to hire engineers and architects for the project. Attempts were made to list the building on the National Register of Historic Places to block the use of Federal funds in the construction of the parking lot. Injunctions were sought for the illegal tree-cutting on the Conrad Hill property, and efforts were made to appeal the Board of Architectural Review being cut out of the process for the Conrad House. As a final attempt, shortly before the demolition PHW ran a series of large advertisements in the Winchester Star alerting taxpayers as to how their money had been used to purchase the Conrad House, and how their money was funding this parking lot against public wishes.

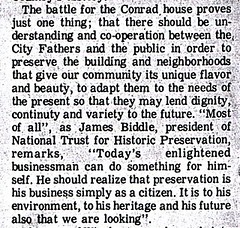

PHW minutes make mention several times of efforts by PHW to invite City representatives to join in meetings, and while politely received, all offers of cooperation were rebuffed. Minutes from February 17, 1970 make clear why: the WPA had called in an unnamed expert from Williamsburg who told them “there was nothing of value left in the house” and “it was not feasible to restore the place.” The minutes go on to record the PHW board’s “consternation over this information” since any expert that looked at the building and site holistically had expressed delight at the structure’s architectural and historical value and integrity. One of the last letters to the editor from R. Lee Taylor, PHW’s corresponding secretary, called for cooperation between the citizens and City Council, for preservation was good business for everyone.(13)

PHW minutes make mention several times of efforts by PHW to invite City representatives to join in meetings, and while politely received, all offers of cooperation were rebuffed. Minutes from February 17, 1970 make clear why: the WPA had called in an unnamed expert from Williamsburg who told them “there was nothing of value left in the house” and “it was not feasible to restore the place.” The minutes go on to record the PHW board’s “consternation over this information” since any expert that looked at the building and site holistically had expressed delight at the structure’s architectural and historical value and integrity. One of the last letters to the editor from R. Lee Taylor, PHW’s corresponding secretary, called for cooperation between the citizens and City Council, for preservation was good business for everyone.(13)

Although the City was not dissuaded from razing the Conrad House in March of 1970, the outpouring of support and frustration via the letter campaign bore some fruit in the end. On April 22, 1970, the City Council and a committee of PHW members met and began taking some of the first steps toward meaningful preservation efforts. The major concession was the acknowledgement that a Board of Architectural Review with purview over only 16 properties was ineffective and invalid, and Tom Scully was granted permission to overhaul the ordinance and present his ideas to Council. The meeting also proposed a strategy to foster cooperation and understanding between the City and PHW by installing PHW members on various boards and Council members partaking in the historical programming of PHW and the Historical Society. Although it took close to a decade, preservation was gaining acceptance in Winchester.

Next week, we will investigate the educational efforts as PHW moved into an era of preservation not focused on the retention of the Conrad House.

Some of the demolished properties which initially concerned the nucleus of PHW in 1963 included Dr. Baldwin’s stone office and the Cannon Ball House on South Loudoun Street, the Capper House on North Loudoun Street, the Chanticleer Inn on West Boscawen Street, and the Hollis House on Cork Street. It appears that these properties were used as examples in the November 1963 meeting at the Handley Library, mentioned in passing in the January 24 post.

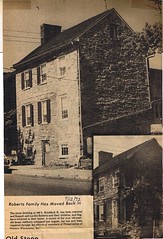

Some of the demolished properties which initially concerned the nucleus of PHW in 1963 included Dr. Baldwin’s stone office and the Cannon Ball House on South Loudoun Street, the Capper House on North Loudoun Street, the Chanticleer Inn on West Boscawen Street, and the Hollis House on Cork Street. It appears that these properties were used as examples in the November 1963 meeting at the Handley Library, mentioned in passing in the January 24 post. Toward the end of the battle for the Conrad House, Hawthorn on Amherst Street was similarly being threatened with demolition for subdivisions for more Whittier Acres construction if the building could not be sold. Although PHW toyed with the idea of buying the property jointly with other civic organizations, the idea did not come to pass and the home was preserved through private efforts. Conrad House enthusiasts may be pleased to note the front porch now on Hawthorn was salvaged from the Conrad House.

Toward the end of the battle for the Conrad House, Hawthorn on Amherst Street was similarly being threatened with demolition for subdivisions for more Whittier Acres construction if the building could not be sold. Although PHW toyed with the idea of buying the property jointly with other civic organizations, the idea did not come to pass and the home was preserved through private efforts. Conrad House enthusiasts may be pleased to note the front porch now on Hawthorn was salvaged from the Conrad House.